ARR? Renewals? Churn? CARR? : A Guide For The Perplexed

I’ve previously covered value realisation and the key metrics you use to understand how your customers are extracting value from your solution. We’ve also discussed NPS and customer satisfaction and looked at ways to measure that as smartly as possible. Now it’s time to look at the vital SaaS KPI of renewal rate.

Renewals & ARR

To understand renewal rate first you have to understand ARR. If you don’t then this next bit is for you. Skip to Renewal Rate if you already get ARR.

ARR?

Subscription companies who write contracts with a minimum term of 1 year usually measure annual recurring revenue or ARR. It’s a beautiful thing as you’ll see shortly. For now though it’s easiest to explain how it works with an example.

I do all of my writing in Ulysses which recently converted from an on-premise model to a subscription model. Rather than a one-off lifetime purchase it now costs me £25 a year to subscribe. It’s a great app and when they changed to the subscription model they offered existing customers a very attractive discount to convert which I did. I chose to convert to ensure I got access to all the upcoming features they had planned and to ensure I could take advantage of their synching tools. In that regard I’m a classic case.

In the example below we’re going to imagine that Ulysses have exactly 200,000 customers, all paying an annual fee of £25, and it’s the start of the first day of their financial year. At that point their ARR is £5,000,000 (that’s 200,000 x £25 for those of you who missed arithmetic class):

- On the first day of the financial year they sign up 400 new customers so ARR increases to £5,010,000 reflecting the fact they now have 200,400 subscribers all paying £25

- The same happens on day two so ARR increases by another £10,000 to £5,020,000

- On day three however it so happens that 1000 subscriptions are due to expire and of those 600 customers renew and 400 chose to cancel. The 400 who cancel can no longer be counted as part of ARR which therefore drops by £10,000 and goes back to £5,010,000. Not a great day for Ulysses.

- This pattern of signing new customers, renewing customers and losing customers continues on a daily basis (it’s a consumer app with a large user base so it will change on a daily basis). By the start of the first day of the next financial year Ulysses have added 40,000 net new customers so ARR has increased by £1,000,000 and is now £6,000,000.

Overall it’s been a good year for Ulysses. But could it have been better? Of course the answer to that is yes and there are two main ways that £6,000,000 number could have been improved, more sales to new customers and fewer cancellations from existing customers. It’s that cancellation number that’s at the heart of why we have customer success and it determines a company’s renewal rate.

Before we move on to look at renewal rate bear in mind you may hear other similar sounding metrics bandied around:

- CARR which stands for contracted (or committed) annual recurring revenue is one that takes into effect known future business and known future cancellations that don’t yet show up in ARR

- MRR which stands for monthly recurring revenue is another and is used where contracts are less than a year in duration (most commonly a month) such as in companies like Spotify.

In fact ARR (or CARR) is commonly used in a B2B scenario and MRR in B2C.

Renewal Rate

Renewal rate, churn rate, attrition rate. These are all terms you hear used to measure the same thing: the change in ARR resulting from customers lost over a period of time. I’ve always liked renewal because it focusses on the positive, the customers I’ve kept in my various customer success roles, but churn / attrition which focusses on those lost serves exactly the same purpose. The only difference of course is you want either a high renewal rate or a low rate of churn or attrition.

Let’s go back to our example above and that bad 3rd day when 400 Ulysses customers decided to cancel their subscription. On that day Ulysses renewed 60% of the ARR up for renewal and churned or attrited 40%. Very simply if we now look across the entire year and add together all the daily renewals to get the total ARR that renews over the year we get the renewal rate (or if we add up the cancelled revenue we get the churn rate).

In the case above starting with the 200,000 customers available to renew at the start of the year:

- 190,000 chose to renew over the course of the year.

- That 190,000 represents revenue of £4,750,000 or 95% of the £5,000,000 ARR that Ulysses started the year with.

- So the renewal rate is 95%.

If that seems very straightforward - that’s because it is. And despite the odd bad day it seems the combination of the product and service is a good one and Ulysses have had a great year.

If you are wondering how all the new customers added during the year factor into this calculation - they don’t. As our example assumes a minimum contract of 1 year none of those new customers renew in the current financial year so don’t form part of the calculation of this year’s renewal rate.

In the real world of course it’s never this simple. Companies will have customers paying a variety of license rates, multi-year or contracts of odd lengths can add complexity, unless you are alert to it important details can be out of sight when you sell multiple product lines in a B2B environment, what you can count as ARR has to be agreed and so on. The important point though is the basic ARR renewal rate is an excellent indication of the health of any subscription business.

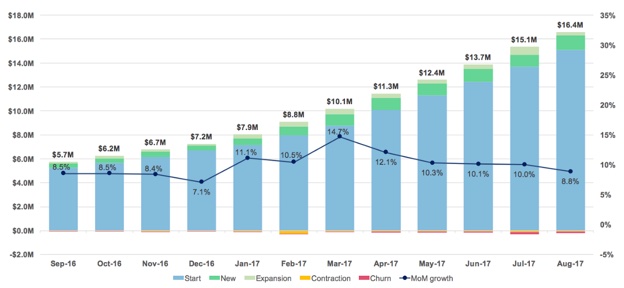

Chart 1 : ARR Increase Over Time

I mentioned that ARR is a beautiful thing. As the chart above shows in a healthy business it grows steadily and remorselessly. Hopefully now you can see why. In my case for example I love Ulysses. It’s a near certainty that I’ll renew my subscription in 5 months time so without them doing any selling: I’m a guaranteed customer. There are many many customers like me so they have a very predictable revenue stream. If they keep up the great focus they have on shipping a world class product and providing their low touch but effective customer success efforts and product support then year on year growth, with such a solid revenue baseline, is far easier to achieve.

This is a huge change from the on-premise model that Ulysses employed until the middle of last year and explains why nearly everyone is moving to subscription. Once you’ve sold your product on a perpetual license (which is what all on-premise licenses were) that’s it. Far less predictable future revenue from that customer. Your best hope is they will pay out again next year for the next major version, or in two years if that’s when it arrives. Lots of customers won’t, they’ll just carry on with the perfectly acceptable version that they already have, maybe skip an upgrade or two and dip in again in 3 or 4 years. Which means to continue to bring in the revenues needed to sustain the business Ulysses needed to acquire far more new customers every year than they do under the subscription model. That’s harder, costlier and far less predictable than the subscription model.

To paraphrase the Emperor in Star Wars.

Now witness the firepower of this fully ARMED and OPERATIONAL subscription licensing model!